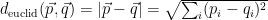

The Euclidean distance between two vectors p and q is the length of the line segment that connects them (here and in all following formulas the sum is over all dimensions of the vectors, i.e., if we have n dimensions the sum ranges from i=0 to n):

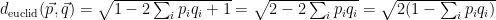

Using the binomial expansion, we can write this as follows:

Unit vectors have a length of 1 (by definition), length is calculated as the Euclidean norm, that is, the Euclidean distance of a vector to the zero vector, i.e., the square root of the sum of all sqared entries in the vector:

If something is 1, its square is also 1:

We can now replace the squared sums over all vector elements in the formula for Euclidean distance with 1:

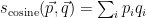

Now let’s see how the cosine distance is defined. The more common thing to do is to calculate the cosine similarity of two vectors as the cosine of the angle between them:

As we have unit vectors, we can get rid of the division by the length (which is always 1), so the formula is simplified to the dot product between the two vectors:

When we have a vector space where the entries correspond to occurrences of terms in a document, all entries are positive, so the value of the cosine similarity will always be between zero and one. This means, we can define the cosine distance as:

So let’s put it together. Let’s say we have two vectors v and w and we know that measured with Euclidean distance, v is closer to some other point p than w is*:

We can now replace the Euclidean distance with the formula from above, square both sides (because that doesn’t change the inequality relation) and get rid of the two that appears on both sides:

What we are left with is the cosine distance! So, putting start and end together, what we have shown is:

This doesn’t mean that when you calculate Euclidean distance and cosine distance between two vectors that you will get the same number. But whenever you are only interested in relative distances (that means you only want to know which of two vectors is closer to something than the other) and you have vectors that are normalized to unit length with only positive entries, then the result should be the same whether you use cosine or Euclidean distance.

* The text says “closer” and not “closer or the same” and that is actually what I wanted to say, but there seems to be some strange bug in this LaTeX plugin that doesn’t allow you to use the < sign in a formula... so we'll take the less-or-equal sign and just ignore the equal-part.